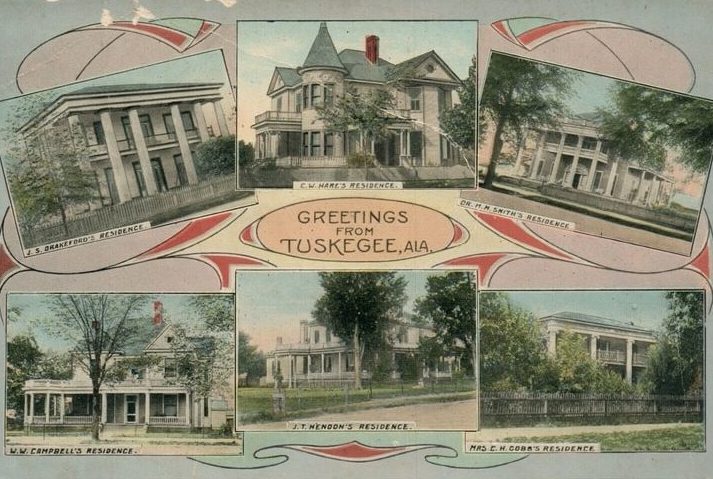

The Sadler House was built in 1895 and occupied by Charles Woodrolph Hare who was an established attorney and political figure in Macon County. Hare was the editor for the Chilton View before moving to Tuskegee after he purchased the Tuskegee News in 1895.

In 1913, he became the president of the Screws Monument Association after publishing a suggestion that Alabama editors should honor the late William Wallace Screws, a confederate soldier, Secretary of State for Alabama, and editor for the Montgomery Advertiser.

In 1913, he became the president of the Screws Monument Association after publishing a suggestion that Alabama editors should honor the late William Wallace Screws, a confederate soldier, Secretary of State for Alabama, and editor for the Montgomery Advertiser.

At the time of Hare’s death in May 1930, he had served two terms as a member of the State Democratic Executive Committee, assistant director of munitions during World War I, and served as director of sales for the state’s war department.

Sheriff James Harvey Sadler

In later years, the home was occupied by James Harvey Sadler who was appointed by Governor George Wallace as sheriff of Macon County in 1964 to complete Preston Hornsby’s term after Hornsby resigned to become a probate judge. Sadler was a businessman having owned Sadler’s Grocery & Market and the Sadler Oil Company and was Wallace’s campaign chairman in Macon County in 1962.

The Shooting of Samuel Younge Jr.

Less than two years later, Harvey Sadler and the city of Tuskegee were thrust into the national spotlight. On January 3, 1966, a black 21-year-old Tuskegee Institute student by the name of Samuel Younge Jr. stopped at the Standard Oil gas station on the corner of North Maple Street and Highway 29 to use the restroom. Instead, he ended up arguing with the white gas station attendant, 67-year-old Marvin Segrest, who refused him access as it was for whites only.

Multiple witnesses said that Younge had approached Segrest asking to use the restroom who replied by telling him he could use the restroom around back. Younge stated he wasn’t going to use the restroom in the back and wanted to use the one in the station. Segrest pulled out a revolver and told him to leave and the two began yelling profanities at each other. At some point, Younge retrieved a golf club from one of the witnesses’ bags. Segrest fired a shot from 80 feet away but missed. Younge ran down an alleyway when another gunshot was heard and he fell to the ground. The autopsy report stated that Samuel Younge Jr. was shot in the face.

Arrest and Trial

Sheriff Harvey Sadler framed the case as a “dispute” rather than “one of these civil rights cases.” It was only after nearly 2,000 Tuskegee students and faculty members demonstrated on the town square, whose centerpiece is a Confederate memorial, was Marvin Segrest arrested and indicted for second-degree murder. His attorney as well as Sheriff Sadler petitioned to have the trial moved to the adjacent Lee County which was overwhelmingly white. Judge L. J. Tyner approved the change of venue, and an all-white jury was selected for the trial in Opelika in December 1966.

During the trial, Segrest gave a three-hour testimony telling the court he had problems with the victim on several occasions. On one occasion, the victim did not pay enough for his gas. The subject stated that when he asked the victim for additional money, the victim threw some money on the ground and said, “There’s the goddamn money. You can kiss my goddamn ass.” On another occasion, the station did not have the kind of gas that the victim wanted.

The victim became angry upon hearing this, told the subject that he was old, and threatened the subject with physical harm. His defense attorney argued that the gold club was seen as a potential weapon and called the shooting an “unfortunate accident.” Prosecutor Tom Young noted that 80 feet were between the two men, adding “I’ve never seen any kind of golf stick that has the range of a .38 pistol.”

Public Response

The jury took only 71 minutes to acquit Segrest of the murder. Upon hearing the news, Tuskegee students rioted in the city’s downtown, hurling rocks and bricks through the windows of white-owned businesses. Leaves and trash were set ablaze in the square and black paint was poured over a Confederate monument in protest. The FBI later reviewed the case in 2008 as part of the Emmett Till Unsolved Civil Rights Crime Act of 2007 but the case was closed as Segrest had died in 1986.

The case marked the beginning of the end for local white power. Soon after the trial, Lucius Amerson, a 32-year-old black man, a former paratrooper, and Korean War Veteran, was elected sheriff of Macon County, defeating Sheriff Harvey Sadler and becoming the first black sheriff in the South after Reconstruction. Sadler amicably took the loss, exclaiming that Amerson would have to “brace his back and face up to the job. He’s now known too well and he must gain the respect of the people.“

Many people were unhappy with the outcome. One white deputy discussed his opinions saying, “the first time a Negro officer puts his hand on a white woman, there’s going to be trouble.” Many whites thought Amerson’s biggest threats were other blacks with one white owner of a used car lot telling a newspaper, “The first time he goes into one of those n****r beer joints and tries to make an arrest, somebody is going to kill him.” Civil rights leader and city council member Reverend K. L. Buford spoke out against Amerson as well saying Sadler should’ve been reelected. Buford later resigned after much pushback from the black community.

Sadler House

The Sadler House is one of eight historic homes that were added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1985 as a part of the North Main Street Historic District.

It is described as a “two-story, Queen Anne, frame house with a corner turret, a hipped roof, and extended cross gables. An original one-story porch that once surrounded two sides of the house has been replaced with two small one-story Neoclassical columned porches. The house has been meticulously restored both inside and out. The interior includes all original woodwork, an unusual stairway with a circular landing at the first-floor level; original, very early electric light fixtures, and all original pine flooring. All windows are original including single panes, diamond glazing, and stained glass panels.“

Today, many of the houses which make up the historic district are abandoned and in varying states of neglect. Other houses once part of the district no longer exist such as the Wright-Varner-Haygood and Hamilton Houses. Plans were made to rehab the nearby John H. Drakeford House but the plan fell through, and the house now sits abandoned. The Sadler House shares a property with the old Callaway House and is currently owned by the Macon County Healthcare Authority. There are currently no plans for either house.